On the role and selection of prescribed text lists

Two documents of interest to English teachers in Ireland were published in April 2023 by the NCCA:

Prescribing texts: report on the role of prescribed text lists in Junior Cycle and Leaving Certificate English and the processes involved in text selection.

A comparative study of Literature in English curricula across jurisdictions, by Dr Bethan Marshall of King’s College London.

The Marshall study is referenced and summarised in the first report, so you don’t have to read both. It examines and compares English curricula in New South Wales, Victoria, Ontario, England, Scotland, Wales, New Zealand and the United States. There were some elements I found problematic and uneven about its approach (especially when it seemed to drift into advocacy), and my post here instead concentrates on the first document, which will be of most interest to other practising teachers.

What does living do to any of us?

I have recently been reading the poetry of Tracy K. Smith. That line appears in her poem ‘The Searchers’, a response to the famous John Ford film starring John Wayne. Like so much of Smith’s work, it is provocative, a questioning of who and what we are. The poem challenges us, it catalyses us into looking from a new angle at just what we are, which is precisely what a poem should do.

‘The Searchers’ is one of 12 poems by Tracy K. Smith which appear on the Higher Level Leaving Certificate syllabus to be examined in 2025. She is a welcome addition to the familiar names of Boland, Dickinson, Eliot, Hopkins, Kavanagh, Mahon and Plath, not only because she is a younger voice with a new perspective as a Black American writer, but because her poetry is truly excellent. It is cheering that work which stretches teachers and students alike comes before us. As teachers we can have issues with plenty of things (I’m looking at you, Paper 1 controversy), but it seems to me that overall text selection is currently done well at post-primary level in Ireland, so we can thank those who have been responsible for the opportunity we and our pupils now have to encounter Tracy K. Smith’s work.

Text selection is central to an English teacher’s professional life - both the texts that are selected for us, the ones we ourselves choose. Teachers of other subjects do not face this process: our Chemistry, Mathematics and Geography teachers rarely have to consider whether or not to prepare a completely new area of their subject for study, especially one that might not even have existed two years ago (as such as Claire Keegan’s Small Things Like These: more on that in the coming months).

Text selection can also bring us into highly contentious arenas, and of course there has always been controversy about some books. The Banned Books Project tells us that

Between 1986 and 2000, at least nine different attempts to remove ‘The Catcher in the Rye’ from schools were based on the novel’s use of profanity and sexual references. Three of these attempts (Wyoming in 1986, North Dakota in 1987, and 1989 in California) were successful in getting the book removed.

By this stage in Ireland Salinger’s novel has lost its controversial charge (I stopped teaching it some years ago, but not because of any controversy - it had simply lost its freshness for me). But book-banning has recently become supercharged in the United States, in places like Florida, as part of a social media-driven culture war which dismayingly has flamed over those most dedicated, modest and admirable professionals, librarians. Book-banning in US schools has risen by 33% in a single year (The authors whose books were targeted were “most frequently female, people of colour, and/or LGBTQ+ individuals”).

As the NCCA document points out, the 2020 George Floyd protests made many here look at choices like Of Mice and Men and To Kill a Mockingbird; on the other end of the political spectrum recently both public librarians and booksellers in Ireland have, appallingly, been targetted by extreme right-wing activists. We should keep our counterparts in Florida in mind, and not assume that never in the future will teachers here be challenged on the books we are teaching by parent groups, by school boards and even by school management (there was a largely risible attempt to do this by right-wing parent-activists a few years ago: the next time it might not be comic). Teachers and schools are also expected to facilitate representative ‘diversity’, an ambition that is almost impossible across a small number of books in a single year (Bennie Kara’s Diversity in Schools: a little guide for teachers is worth reading for some guidance).

These various tensions remind us that what we teach and study sometimes raises hackles because it matters, but we should also always bear in mind that literature is not merely ‘representative’ and ‘relevant’, and our prime duty is to present the children we teach with quality. You can never tell what impact a book will have. Teenagers can be profoundly affected by literature with no direct connection to their lives - Jane Austen’s Emma, Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, Shakespeare’s Hamlet. The populist tendency in America in particular has been to assume that texts must speak directly and simplistically to the details of children’s lives, and that anything older than the contemporary is irrelevant. One of the most profoundly influential writers for me in my own schooldays was Gerard Manley Hopkins - a person with whom I share nothing at all in terms of background, character, profession, sexuality or sensibility.

On to the NCCA document itself. The chapters deal among other issues with the background to prescribed lists, the historical context in Ireland, current processes for Junior Cycle and Leaving Certificate and international research. The historical overview makes it clear that text selection in the early decades of the state was ‘handed down’ from on high, with little input from classroom teachers (an echo of this was heard in the Paper 1 edict, since reversed). Thankfully the composition of text committees is now quite well-based, with good representation from the teaching profession, and sensible criteria on which to base choices.

One repeated note is the idea that no matter how wide a prescribed list, and even in the case of no prescribed list at all (see page 11 for the Junior Certificate syllabus in 1989), a ‘narrow’ choice might be made by teachers and schools. For instance, on page 11 a table shows that in 2006 43.1% of candidates wrote on Romeo and Juliet in the JC Shakespearean drama section, and 42.3% on The Merchant of Venice. In the fiction section the %s were: To Kill a Mockingbird (31.8%), Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry (19.2%) and Of Mice and Men (13.9%). A few pages later the report states that

the Chief Examiner’s Report for the Junior Cycle Examination in 2017 suggests that the full range of texts has not yet been embraced in the system, “Evidence in 2017 suggests that texts commonly used by candidates in the previous Junior Certificate examination, paper two, continued to feature prominently in the 2017 Junior Cycle English examinations. This suggests that the opportunity to engage in reading as a rich and diverse experience is not being availed of to the greatest extent possible”

The stated aims of the curricula have encouraged wide reading and the absence of text lists has, at times, been implemented to discourage a narrowing of focus to minimum texts for examination purposes. The subsequent chief examiners’ reports, however, show that the opposite occurred, and that the absence of prescription resulted for the most part, in a very narrow selection of texts for study. The current situation, where there are prescribed lists for both Junior Cycle and Leaving Certificate English would seem to promote a wider reading of texts.

However, the chief examiners’ reports on, and the media attention to, certain traditional texts would seem to suggest that the broad lists may often be reduced to the more familiar, traditional texts for examinations.

and

Awareness and exploration of an increasing broad and diverse range of texts is an inherent aim in the specifications and so the narrowing of student experience of literature would limit the intended aims of the specifications.

This attitude from officialdom is patronising and unsympathetic. I am a highly experienced teacher, a voracious reader, and a single subject specialist. I love the opportunity to explore new writers for teaching (as with Tracy K.Smith at the start of the piece). However, the reality for so many teachers is that they are deluged with work that makes planning for new material stressful, they are often not English specialists, they may be teaching multiple subjects (say, History and Irish alongside English) and their own reading is not very extensive. They may have, with hard work, built up helpful resources on a text that they are reluctant to abandon. Across six years the English teachers in my school are handling over 20 books and a large number of individual poems. That should not be presented as laziness, and labelled ‘narrow’ particularly by those who have no idea what it is like to have 30 lessons a week with large classes and the concomitant marking load.

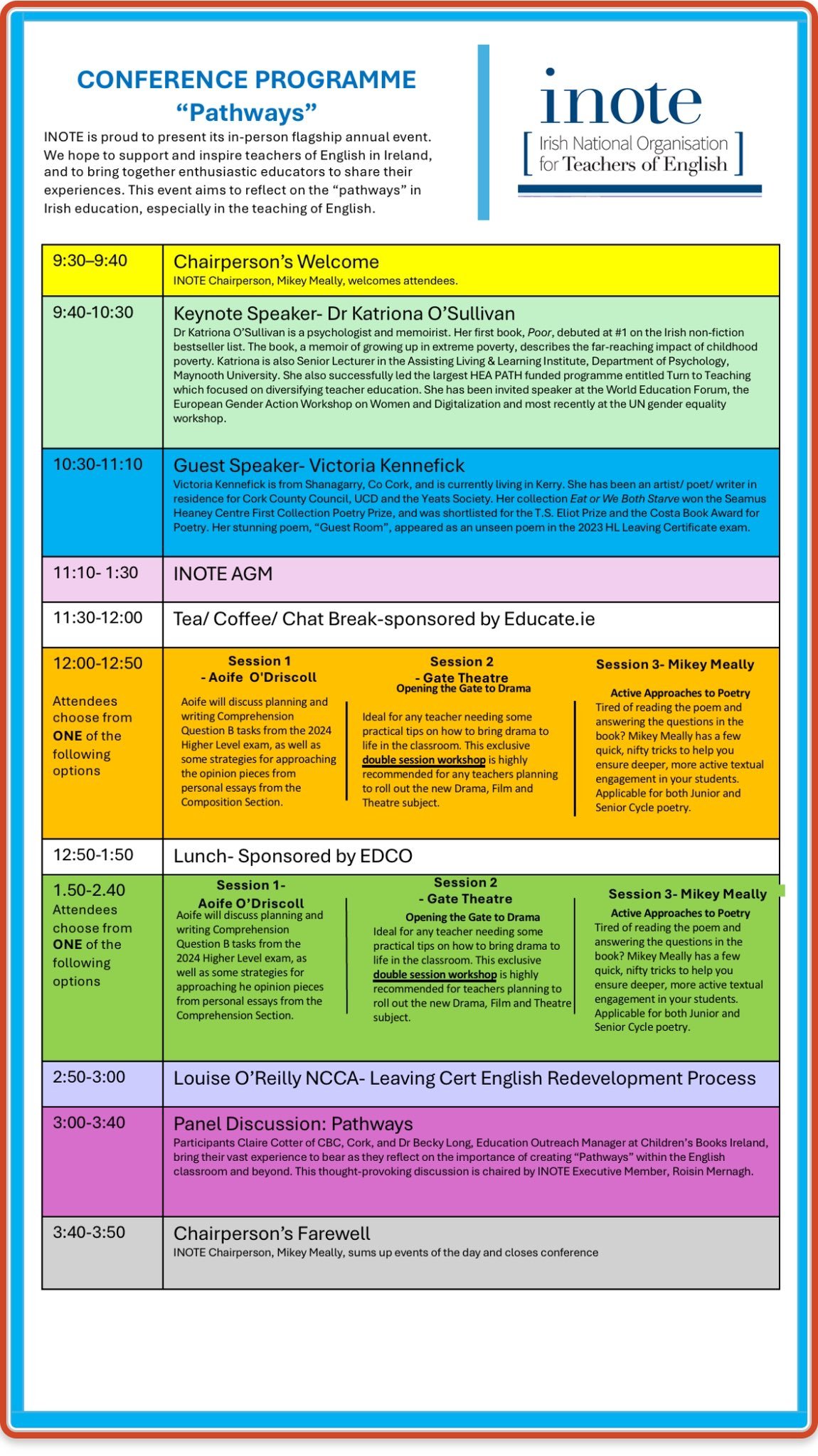

Good prescribed lists (as I think the current Leaving Certificate ones are) should be compiled by experts who point the way for teachers towards interesting and appropriate texts, but teachers who do not have extensive departmental support cannot be expected to research these lists at their leisure. Having been compiled, in Ireland prescribed text lists are just dropped on schools as bald Departmental circulars without any explanation, resources or further encouragement to teachers to explore more widely. Pages 26 and 27 of Prescribing Texts do indeed comment on the time pressure experienced by teachers and the thinness of official support (the best support comes through INOTE and Education Centre webinars). There is also the anxiety that some teachers feel due to ‘increasing media and social media interest’. As English teachers we are on the front line of cultural conflict: our Physics and Applied Mathematics colleagues are never faced with such pressure.

Prescribing Texts ends with three ‘Next Steps’: that decision-making protocols for text selection are developed for the appropriate bodies, that the terms of reference for the membership of the text list committees along with application processes are developed, and that there is

Continuation of work with the support agencies and INOTE to develop awareness and resources for new texts, alongside consideration of further ways to support teachers in dealing with sensitive issues in class.

The last one is I think the most significant, and is an admirable aspiration, but the history of such support from official bodies means that I am not optimistic about such development.

For the moment, let us be thankful that text selection is one of the areas of secondary education is quite well done here: the text list criteria are sensible (pages 18 to 21), the working groups are well-based (page 61), and the results are that English teachers are able to teach a wide range of interesting books, from the classical ‘canon’ to a good range of contemporary work.

Initial thoughts on the Draft Curriculum Specification for Leaving Certificate English (February 2025).