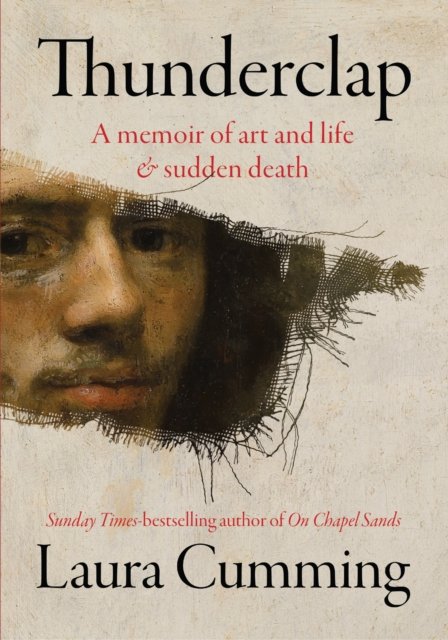

Laura Cumming's 'Thunderclap'

In the summer of 2019, the year before international travel became becalmed across the world, I was in Amsterdam and once again visited the Rijksmuseum. This post explains how I was particularly arrested not by ‘The Night Watch’ or any other of the familiar superstars of the collection, but by a small group of still lifes by a painter I had never heard of before, Adriaen Coorte (c. 1665-1707/10). In particular his ‘Still Life with Asparagus’ grabbed my attention:

About 20 spears of asparagus (a guess - we can’t see the depth of the bunch) are tied together by some twisting russet-coloured string. Poised on a cracked stone tablet, they loom out of a richly dark background. Coorte’s skill is seen particularly on the left-hand side, where some of the spear-ends overshoot the others, somehow semi-transparent against the blackness. They are delicate and luminescent, presenting themselves confidently to the viewer as objects worthy of our sustained attention.

Why did I look at this for a long time? Because this painting and its companions present us with images of what attention might be, in a world in which attention seems to be under increasingly severe threat.

Laura Cumming’s marvellous Thunderclap: a memoir of art and life & sudden death is not about Coorte but rather the mysterious artist Carel Fabritius (actually, it is about far more), but 138 pages in there is the bunch of asparagus, followed by 8 beautifully-written pages on Coorte. The asparagus in this book is another version, held in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, near which I lived for three years.

My gratitude to artists is unending. And to me these paintings by Coorte are life stilled, dense with the time taken to paint them, and the appreciation of what is painted. They are not peaceful so much as pointed, not sedative, but poised in wonderment and awe. They slow my eyes and my thought, and they help with that hardest of all questions – how to live in the here and now.

This is just what I feel, too, and why some paintings move me so much, though naturally I have my own list accumulated over the years (pieces here on Caravaggio’s ‘The Taking of Christ’ and Bruegel’s ‘Hunters in the Snow’; one coming too on Caillebotte’s ‘Paris Street: Rainy Day’). As Cumming writes,

What you see is what you see, yours alone and always true to you, no matter what anyone else contends.

All of which is an appropriately roundabout way to approach the central figure in this book. Carel Fabritius died suddenly in the catastrophic ‘Thunderclap’ gunpowder explosion in the close-knit city of Delft on 12 October 1654, aged just 32. Only about a dozen paintings survive, most famously ‘The Goldfinch’ which I have seen in the wonderful Mauritshuis, but also in a tiny but spectacularly high-quality exhibition called Vermeer, Fabritius and De Hooch: Three Masterpieces from Delft at the National Gallery of Ireland in 2009. Cumming has been obsessed with Fabritius since as a young woman she got to know ‘A View of Delft’ in the National Gallery of London, which to her has

The atmosphere of a memory of a waking dream.

Thunderclap mulls over the gaps in our knowledge of the painter, covering along the way many of the great artists of the Dutch Golden Age, like Avercamp, Ruisdael, Van Goyen and the two most famous names connected with him, Vermeer and Rembrandt. But along that way she does so much more: her attention moves to her own daughter, to the personal tragedies of everyday life, to the extraordinary culture that produced such a high number of masterpieces:

Art proliferated in the new Dutch Republic as nowhere else and as never before. Somewhere between 1.3 and 1.4 million paintings were produced by between 600 and 700 painters in not quite two decades at the mid-century, according to scholarly calculations; though other estimates run as high as 8 million.

Above all the book moves, in indirect and unexpected ways, to the author’s father, the Scottish painter James Cumming. Her previous book, the brilliant memoir and family history On Chapel Sands, unpicked her mother’s story. This one is essentially a love letter to her other parent, bringing him back to her and meditating on his art:

It is a hundred years since his birth, his origins in Scotland, and I only hope ever to hold myself up to his standards of looking and seeing.

In this luminously written book, she certainly has done so.