Bruegel and the cover of 'Small Things Like These'

The first time I visited Vienna was in a December years ago. A snow-storm was raging as I emerged from the airport to find the train into the city centre. Being Vienna, of course everything worked: the kind of weather that would have seized Dublin in a panic was just disregarded, and the succeeding days in the beautiful whitened city were a delight. I’ll be back in a few weeks, again eager to sample the delights of the Christmas markets, Café Diglas and the Kunsthistoriches Museum.

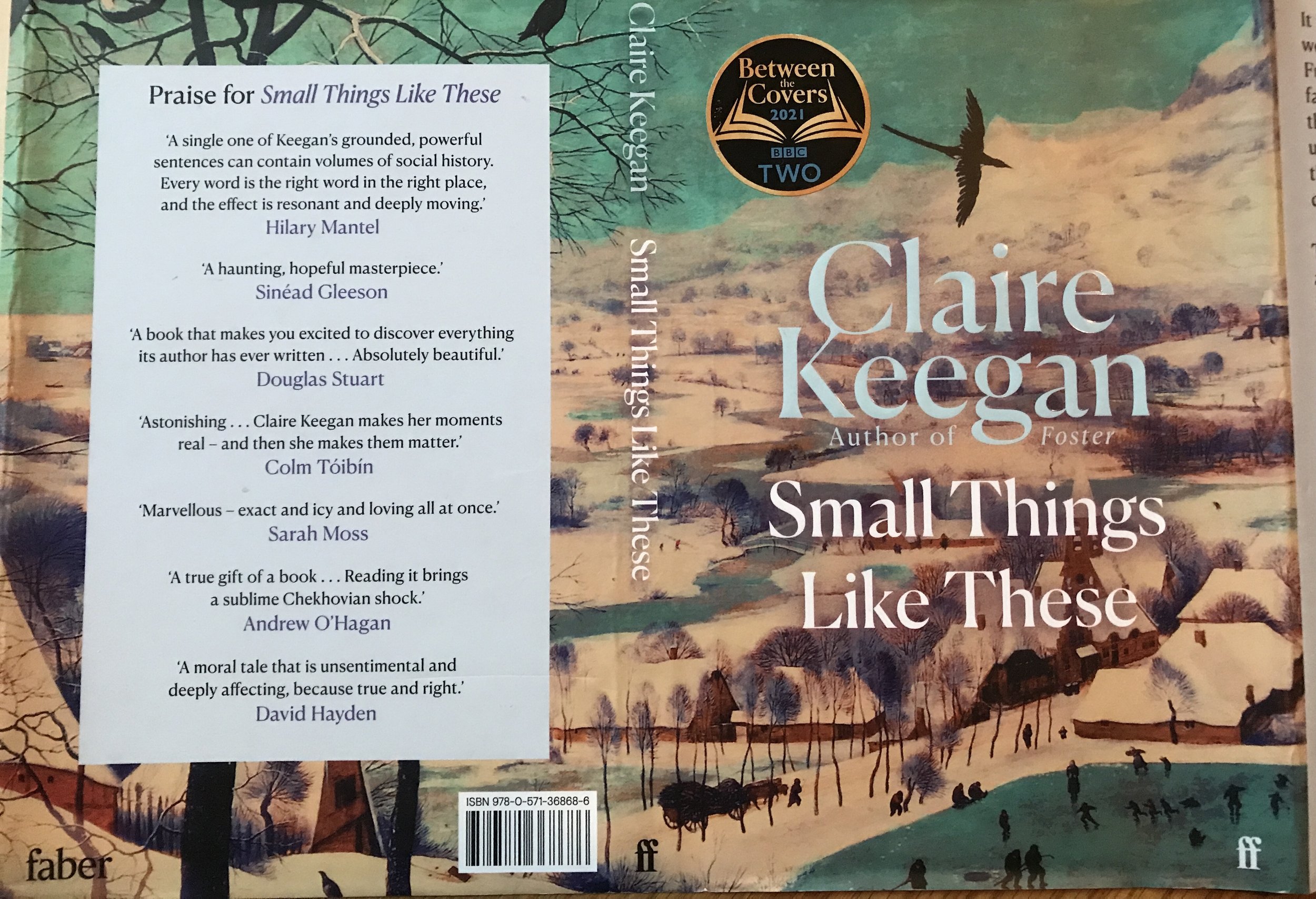

That great art gallery has a total of 12 paintings by Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1525?-1569), more than any other place in the world. Among them are three of the Seasons group, including Winter (Hunters in the Snow, 1565). A section of this was chosen as the illustration for the hardback jacket of Claire Keegan’s short novel Small Things Like These, my book of 2021.

The cover is lovely, and has been a factor in the success of the book. But it is not ‘merely’ decorative. Here are some observations, leading up to a very small, but significant, detail. At the end of this piece, that detail is magnified and set on its own.

The original painting. Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, Gemäldegalerie.

First, the original painting. It is a portrait of an ordinary community in winter (as in Keegan’s book), in the Low Countries in the mid 16th century. The largest figures are on the left, hunters returning from a seemingly unsuccessful day out (one fox caught, downbeat body language). Accompanied by their dog pack they seem to be heading back to the cluster of community buildings, in front of which is a frozen pond, on which men, women and children are skating and playing games. Above those people is the dark silhouette of a crow, prominently above the author’s name in the jacket cover.

Selection for the cover of the novel. Original in Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, Gemäldegalerie.

Now, the section of it selected for the cover. The yellow grid above indicates more or less where it comes from, with the right-hand side the front cover, and the left the back (a large box of recommendations obscures most of the details there). This part of the painting is indeed the cynosure: the gaze of the hunters, the elevation of our own view in this impossible Low Countries landscape, the reducing line of the bare trees, all force our eyes to the pond. This is its subject: ordinary people in a community in winter, in what would have been a hard life, making the most of what they had. The proportionately larger space given to the flying bird reminds us that those creatures haunt Keegan’s narrative ominously: at one point in the December of crows Furlong came across a black cat eating from the carcass of a crow, licking her lips.

But tantalisingly just out of ‘shot’ there is a very suggestive detail.

Immediately below the selection for the jacket cover is a figure crossing a bridge, sticks over his (her?) shoulder. In other words, someone providing fuel (like Furlong), dutifully working hard as others are enjoying their winter sports. Perhaps s/he is heading up to the only source of colour and warmth, the figures close to the hunters who are building the fire outside the Golden Deer inn for the traditional December pig-singeing. Or perhaps to one of the houses arranged down the slope.

Those familiar with Bruegel will think of another painting, ‘The Fall of Icarus’ in the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Brussels (1560s, copy of lost original?) and of Auden’s famous words in his poem of the same name:

In Breughel's Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away

Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may

Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry,

But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone

As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green

Water, and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen

Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky,

Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.

In pretty well the same position as the bridge figure in the Winter painting, Icarus splashes into the water. Auden states how the Old Masters

Understood suffering:

Its human position; how it takes place

While someone else is eating or opening a window or just

walking dully along.

This is indeed the story of Claire Keegan’s novel: terrible suffering was taking place as the rest of us walked dully along; as a society, we knew what was happening, and yet turned away. I explore this idea in my post comparing her book to Fintan O’Toole’s We Don’t Know Ourselves.

The novel tells the story, however, of how Furlong, the fuel merchant, did not turn away from the suffering he witnessed, possibly at great personal cost. A decent father, husband and employer, he worked hard to provide for all, and he took on the responsibility for what he saw when he had to. There must have been other decent people who challenged the darknesses of our history, forgotten now, out of the frame.

Finally, my photo with its companions from November 2022, in situ in the Kunsthistoriches Museum.