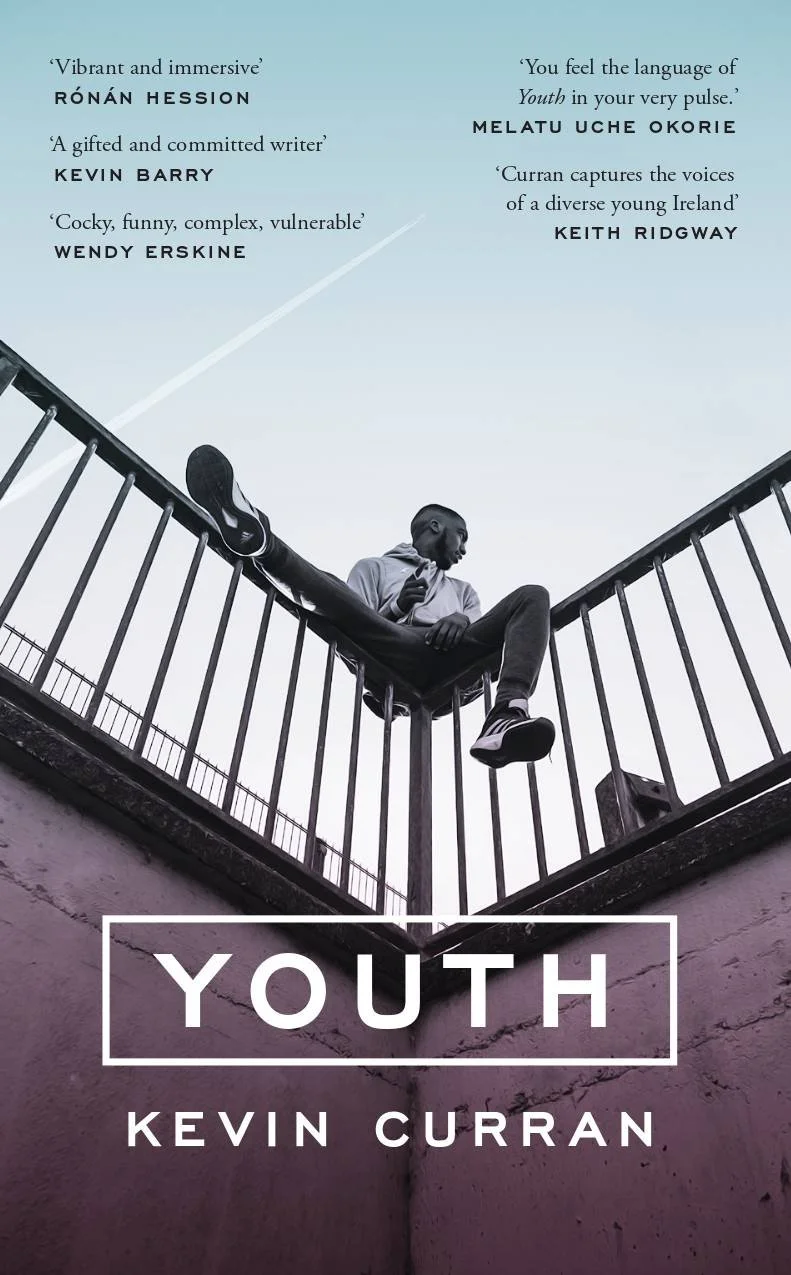

'Youth' by Kevin Curran

Kevin Curran’s fine new novel is ambitious. Expansively titled (Tolstoy, Conrad and Coetzee chose it too), its excellence is in particularities, the fine detail of the lives of four teenagers in a specific place at a specific time. As Patrick Kavanagh wrote in ‘Epic’

I made the Iliad from such

A local row.

The specificities are above all in the textures of the voices of those young people, right from the first paragraph:

(Angel, 18) He speaks in your voice, Dublin, and there’s something hopeful in the new edges of his words and phrases that has come through revolutions, generations, and across continents to be witnessed here, on these streets now.

In Balbriggan, North Dublin, now Ireland’s most diverse community, the four are trying to navigate a lot: school, family, the influences of modern ‘socials’, gender expectations, race. Kevin Curran switches regularly between Angel, Princess, Dean and Tanya (the latter trying to coping with the online world, simultaneously sophisticated and desperately vulnerable - I almost had to turn away from her). As a narrative structure, that is ambitious: there are balls in the air all the time. Most ambitious, however, is Curran’s imagining of lives at such a transitional moment in their lives: it is brave to put down on the page voices which so completely come from their specific ages, cultures and are on these streets now. Teenage argot moves rapidly: Holden Caulfield would be 88 now. The author is an English teacher, and nothing is less cool than a teacher pretending to be down with the kids (I speak from experience): by your mid-20s, you have definitely lost touch, you are definitely old. However, Curran spoke at the launch of the book about the care he took to get prolonged feedback from a group of Irish-Nigerian girls, and this is clearly seen in the strand of the book that most moved me.

Princess is wonderful: determined, resilient. Her first line is Don’t. Have. Sex. She cannot afford to become pregnant like her sister. The local library is important to her: she needs to study and cannot do that in her crowded home. She wants to be a pharmacist, inspired by the example of Tunde, who ran a pharmacy now closed due to the arrival of the chain-store Boots:

Mine will be a family one. On the main street. Like Tunde’s used to be. Adedokun Pharmacy. And the flashing green light will be a beacon for all. A sign to say I will look after you. I will accept you. If you are sick (and you have money) I will serve you, care for you, no matter who you are. And I will wear the white coat with the name tag: Princess Adedokun, Pharmacist.

You feel for her, fear for her, as the story progresses and as the other characters also try to find their way to what they will be. The narratives intertwine, but they do not move towards a simple plot resolution, and there cannot be one. As I write this, my own pupils are finishing their Leaving Certificate, poised to go out into their lives. Right now is youth, and all the rest is yet to come.