William Wall's 'Smugglers in the Underground Hug Trade'

I really have no enthusiasm for reading a ‘pandemic novel.’ Most of us have had quite enough reading about ‘it’ over the last 18 months, and a pleasure has been to turn off the news and fold the paper, and turn to novels set in early 1930s England, or early 20th century German East Africa, or New Ross in the 1980s, and lose ourselves in other worlds (though Hamnet was a bit too close to the bone).

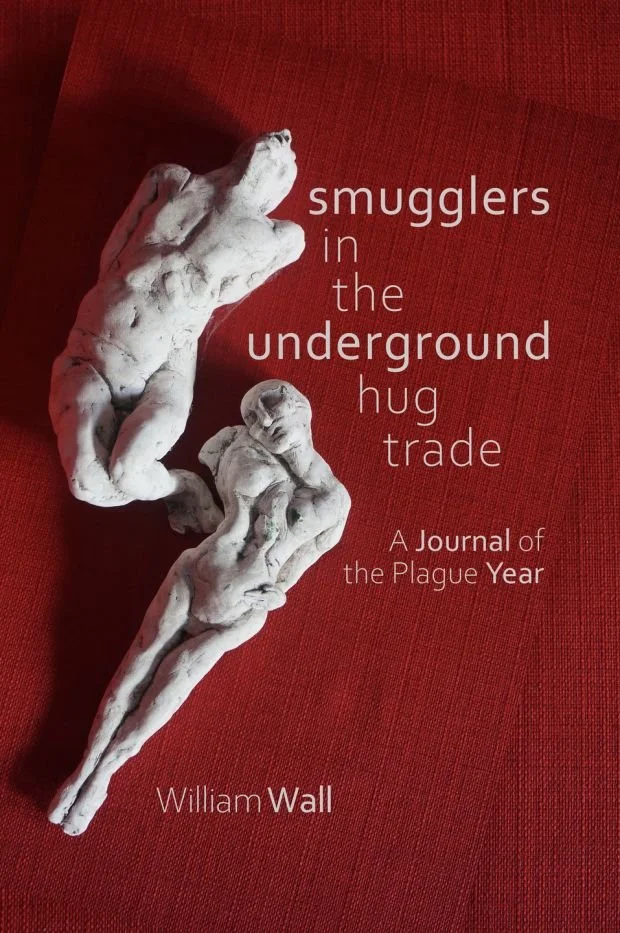

However, I did find myself buying, reading and enjoying William Wall’s Smugglers in the Underground Hug Trade: a journal of the plague year (attractively produced by Doire Press). It is a sequence of poems set in 2020, describing and reflecting on the author’s life in the first year of the pandemic. Each poem is dated (some, like one on Trump visiting the CDC, reminded me a little of Nick Asbury’s poetic responses in his Realtime Notes). The lines are unpunctuated, note-like at times, almost jottings. The range is wide: there is anger here, and anxiety, but also an appreciation of beauty, and the underlying love story of Wall’s companionship with his wife (we survive by loving / one morsel at a time: the ‘we’ of them as a couple sometimes feeling like the ‘we’ of all our experiences). He puts our experience in the context of other plagues, referencing Defoe (as in the sub-title, of course), Camus, Pepys, Thucydides, Manzoni, Dante Alighieri and Boccaccio.

Things Italian appear throughout the sequence. In the second poem, ‘Porto Corsini’, Wall is in pre-pandemic Liguria:

from the pier at Porto Corsini

we leave the open sea

a voyage to the interior

that weaves a gleamingbasketwork of memory

and forgetting

But by February 24th (‘La Quarantena’) the virus has come uncomfortably close, and he thinks of Florence in 1630:

they traced the chicken vendor

and his family

they traced his contacts

they closed the border

and still it came

the plague is out

no holding it now

By February 26th in ‘Flight to Ireland’ we are fleeing the epidemic via a deserted Fiumicino Airport in Rome, and the rest of the book is set in County Cork. Like everyone else in those early months, Wall takes consolation from small things, especially the natural world. The sea (and the local beach) is a strong, and comforting, presence throughout (‘The Receiver of Wreck’, ‘In the Declining Evening I Swim’, ‘You Walk Away - on the lifting of lockdown’, ‘We read The Inferno at the Beach’, ‘Even the Orcas’ among other poems), though there are darker connotations of water too (the successive waves in the strangest year we have lived; his body being the shipwreck of bones; the virus being a floating mine /drifting among shipwrecked souls).

By December 2020, and the final pages of the book, Wall has been through the ups and downs everyone else experienced. On December 5th there is a lovely poem called ‘The Jewish Cemetery’ about the late David Marcus, who I once spent time with at the Irish Press offices in Burgh Quay (he was kind and perceptive about a story written by a callow young man). In ‘Christmas’ the day

dawns bright

all the open doors

memory in the mist

over the valley

here’s to absent friends

There is ease and libation as four glasses of wine are poured. And now here we are, at the end of 2021, facing another uncertain Christmas, and we will treasure simple things, and family, and friends, and libation.

On December 31st he ends with ‘O You Who Come to This House of Pain’, with its refrain watch whom you trust and how you go / these are the dark days. But there is a final hopeful note, quoting Camus:

Finally, in the depth of winter I learned that there was in me an invincible summer.

and in the final sentence of the Notes which follow the poems he writes that hope for the future lies in the vaccine.

As we now know, there was much more to come, but his book is done. It would be hard to imagine a 2021 version: is there more to say? For how long can poetry respond directly to this event without burning out?

On December 5th, in the poignant ‘In Memoriam’ he thinks of the death of a middle-aged hairdresser:

but you went to get your hair cut

and his daughter told you the news

he used to say your hair was beautiful

he understood its fall

at the scale of the everyday

these things are colossal.

Just so: what we have experienced has felt colossal at the scale of the everyday, and Wall has given us a memorable record of just what that has been like.