Technology for Teaching: a personal history

In the middle of this remote reaching blizzard - Zoom! Loom! Google Meet! Seesaw! - I thought I’d reach back to earlier forms of teaching technology. I’m old enough to have used a lot in my pre-computer teaching career that is now obsolescent (like I will be before long), and indeed forgotten (again…). I’ve always been a gadget fan. (Here some thoughts on the online classroom).

This is prompted by Mary Myatt’s excellent post on photocopying in which she considers that ubiquitous technology in terms of environmental and financial cost, but also less obviously in how it might actually distract us from what is essential:

Essentialism asks us to go back and ask these awkward questions. It’s not as though teaching and learning didn’t happen before the advent of photocopying. Decades ago, there were Banda machines - inky, oily and messy, so teachers had to be really clear about the benefits of copying off if they were prepared to go through this rigmarole. Funnily enough, learning still took place even before the Banda machine was invented.

Well, reader, I’m old enough to remember the Banda. So we’ll start there.

1980s. I started teaching in the middle of the decade. The Banda was a form of spirit duplicator (see Gestetner, below). As a teacher, let alone a very junior one, you certainly didn’t stroll along and use it yourself. No, no - in most schools there was a gatekeeper (usually the very important secretary), who used the machine primarily to crank our mauve-coloured lists and other significant administrative documents. But you might be able to book a brief space in which to run off a few poems (also mauve-coloured, and subject to fading) for distribution in class. In the words of Wikipedia:

The faintly sweet aroma of pages fresh off the duplicator was a feature of school life in the spirit-duplicator era.

Better still, Rosemary Hampton has a detailed illustrated explanatory piece here.

The Gestetner machine was a step up. If you have a lot of time to waste right now, AIGA, the design association, gives you a deep dive.

But now back to the most reliable tool of all, the blackboard. Yes, your hands and clothes were permeated by dust, but a good board (the quality was erratic) when combined with decent sticks of chalk was such a joy. The wonderful friction! A distinguished former colleague’s boardwork for Biology class was glorious, with colour masterpieces demonstrating an insect’s body or a plant’s stucture (and it was all rubbed off immediately afterwards).

Now enjoy yourself with some blackboard and chalk porn, in which Harvard Mathematics professors talk about their love of the medium. Look at those multiple boards! And the ‘chalk-dealing’… The chalk in question is Hagoromo Fullchalk.

That video came from Oliver Knill’s post ‘About Blackboards’:

Blackboards are terrific. It is probably the overwhelming opinion that in mathematics, blackboards are the best tool to develop a thought to a class. They always work and they slow down the speaker enough to get the ideas across clearly. Powerpoint needs lots of restraint in order to be used effectively. It is rarely done right.

‘They always work and they slow down the speaker.’ Just so for English as well as mathematics.

In 2014, the late Mary Mulvihill echoed this in the Irish Times with her article on ‘saving the blackboard’ from the perspective of a science teacher. And here’s Lewis Buzbee on ‘The Simple Genius of the Blackboard.’

Next, the typewriter. During the ‘lockdown’ summer of 2020 I cleaned up mine and bought new ribbon (top photo), bought new in the 1970s (I recommend this post on typewriters by Kenny Pieper). I still have some of the materials typed up in the early part of my career: they’re noticeably shorter than the PC/photocopied/VLE version of today. Again as Mary Myatt points out (see above), the sheer ease of photocopying challenges ‘essentialism’: similarly, the typewriter meant you needed to be careful producing class material. Nowadays we just blast away at the laptop keyboard, certain that later we can correct and adjust. Then, minor changes only could be made via the Tipp-ex bottle or the paper version (or, more excitingly, later on the ‘Pocket Mouse’ which spewed correcting tape out of its mouth).You needed to avoid knobbly white clumps (a niche in the market addressed by Tipp-ex Thinner). Wikipedia rabbit-hole: Tipp-ex was bought by Bic in 1997.

On to the overhead projector. This lasted quite a while, until the fixed classroom projector and attached device took over. Jargon: ‘transparencies’, OHP.

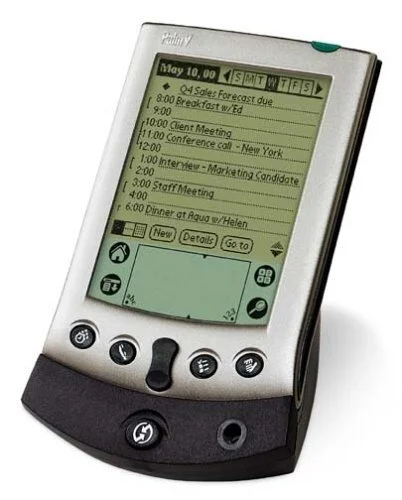

The online world crept into education very slowly, firstly as email. Brief shout-out for my favourite-ever ‘organiser’, the Palm V (brushed metal, stylus with handwriting recognition, launched 1999), onto which you could download what we now know as apps. It was so excitingly futuristic to carry files, schedule, and notes in your pocket: 007 territory.

Richard Baguley on The Gadget we Miss:

It approached the idea of perfection in both form and function: it looked beautiful and did a great job of providing the features that people actually needed, rather than the ones that designers thought they did.

Once the classroom projector took hold the visualiser, or document camera, became possible. Simple, versatile, effective. In the Covid-19 compliant and remote classrooms it’s had a boost recently, and I wrote this piece about using it for English. Wikipedia again (though this could be a mischievous editor):

The device has sometimes been called a "Belshazzar", after Belshazzar's feast: "In the same hour came forth fingers of a man's hand, and wrote over against the candlestick upon the plaister of the wall of the king's palace: and the king saw the part of the hand that wrote" (Daniel 5:5).

Things I haven’t mentioned: cassette tapes, slides, floppy discs, VHS and the video/TV trolley. I managed during my career to avoid interactive whiteboards.

And so back to Mary Myatt’s statement that seeded this post:

Funnily enough, learning still took place even before the Banda machine was invented.

As Daisy Christodoulou has pointed out in her recent Teachers vs Tech? the case for an ed tech revolution, the history of technology in education is riddled with over-promise: some of it has worked well, some has crumbled into the deserts of time. In not so many decades we’ll certainly look back at how quaint, inefficient and awkward were the technologies of 2021: laptops, iPads, Google Classroom, Teams, Zoom and the rest.

As I said, I like gadgets and technology: it’s the little boy in me. But, finally, the perfect irreducible technology for an English class is: a room, books, pen, paper, a teacher and pupils in discussion, in common purpose.