R.F. Foster's 'On Seamus Heaney'

The first time I met Seamus Heaney, I was in my mid-teens, a gawky bookish schoolboy. He was already famous, but he treated me as if I and my opinions mattered, as he did with everyone: I have never heard of anyone who said otherwise. He gave time and attention to every individual person.

Roy Foster’s short overview of Heaney’s career highlights how extraordinary the pressures on him were, how much he did for so many people and how, amazingly, he managed in the eye of that storm to write such resonant works. He did that consistently throughout his career, even when the demands threatened to become overwhelming. Foster cites the ‘roster of commitments’ in 2021, as detailed by Dennis O’Driscoll in his vital book Stepping Stones: even reading the summary of that year exhausts you.

On Seamus Heaney is in the Princeton University Press series Writers on Writers, which includes Colm Tóibín’s On Elizabeth Bishop, which I recommend. In just over 200 small-format pages, somehow Foster manages to cover the sweep of this fecund and productive career with total command, seeing Heaney in his wider context and also digging (ha) into individual poems. He is careful in his judgments and not a thoughtless booster (he calls the collection Electric Light ‘markedly uneven’, maybe due to a post-Nobel effect).

Many of the best-known poems, often staples of English classes, are covered here - ‘Mid-Term Break’, ‘Clearances’, ‘Postscript’, ‘The Tollund Man’. I have an abiding affection for the elegiac 1979 collection Field Work, which I see from an inscription I bought in October of that year (its original cover art work was autumnal in colour, centring a map of Glanmore in County Wicklow). Foster mentions the marvellous ‘The Harvest Bow’ from it, which is also in the current Leaving Certificate selection, and which, more subtly than ‘Digging’

delicately enshrines in ‘a throwaway love-knot of straw’ his memories of paternal closeness and unspoken affection. The loops of the straw emblem are a kind of magic lens through which a family history is envisioned, rather as a seashell may be listened to for the sound of the sea.

The other day I again taught another poem about his father (his mother appears too), ‘A Call’, which has a final line as poignant as that of ‘Mid-Term Break’, and thought of Foster’s penultimate chapter ‘The Bird on the Roof’. There he looks at the final collection, Human Chain (2010), the poems in which are economical but powerfully substantial. An example is the sequence ‘Album’, which invokes

The heartbreaking scene in ‘Aeneid VI’ where Aeneas tries to embrace his father in the shades, and repeatedly finds the insubstantial form sliding away from him: reprised by Heaney in light of the shyness that inhibits expressed affection.

In section IV he thinks back, as he approaches his own old age, to when he might have embraced his father in his prime, then did so on an occasion when the older man was the worse for wear for drink, and finally

On the landing during his last week,

Helping him to the bathroom, my right arm

Taking the webby weight of his underarm.

In the next section,

It took a grandson to do it properly,

To rush him in the armchair

With a snatch raid on his neck

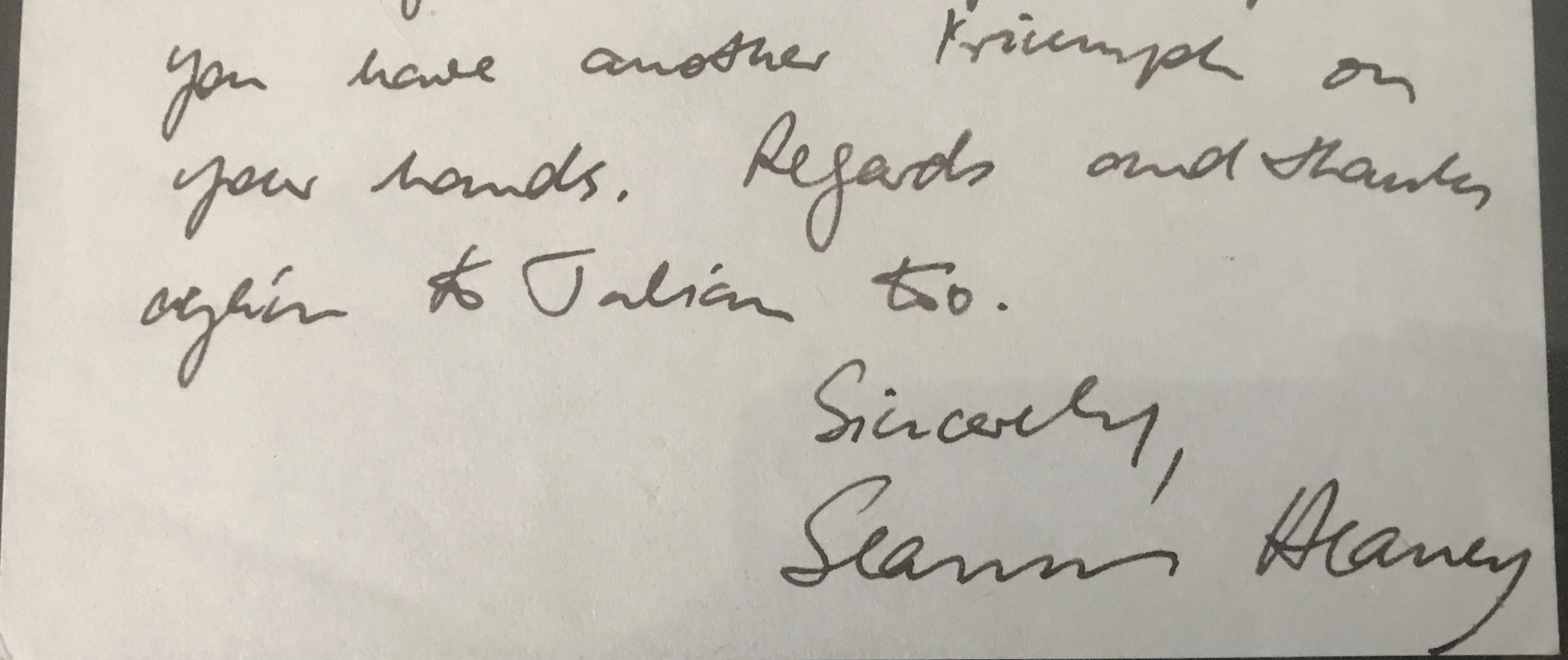

My encounters with Heaney were through my own father, to whom in 1983 he wrote a thank you letter, signing off with good wishes to me. Both men have gone now, but Roy Foster’s book is a lovely way to revisit the poet’s oeuvre and remind us of the heartening breadth of his achievements, which continue to buoy us up.

Below, Roy Foster talks to Catherine Heaney, Seamus’s daughter, about the book.