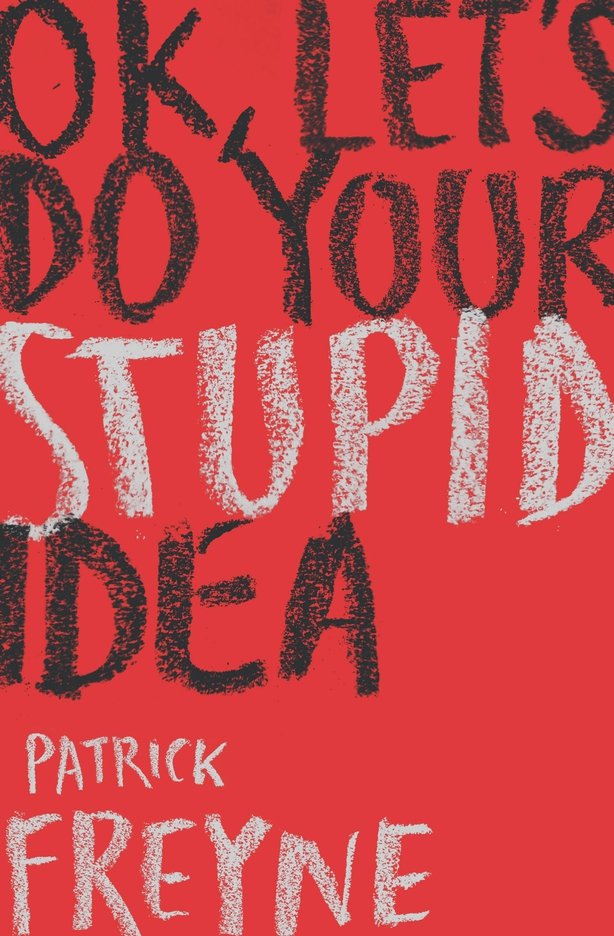

Patrick Freyne's 'OK, Let's Do Your Stupid Idea'

In Minds Made for Stories (2014), his examination of non-fiction writing, Thomas Newkirk wrote about Siddhartha Mukherjee’s Pulitzer Prize-winning The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer:

What I got was the experience of being with the author as he led me through the cycles of hope and defeat … The great value of works like this, like good fiction, is that we put ourselves in the hands of someone else… We sign on for the journey. To be taken into a book like The Emperor of all Maladies is to move outside ourselves … to experience another sensibility, to sense how the writer notices, contemplates, values. I suspect this fellow-travelling is the great lasting benefit we get from sustained reading of good nonfiction, one that seeps into our writing - or so we hope.

Patrick Freyne is best-known in Ireland for his Irish Times writing, including television programme reviews on the likes of Buying Beverly Hills (‘Selling Sunset meets King Lear’), and a wide range of feature articles. He has a talent for humour (more Clive James than the harder-edged Marina Hyde, perhaps), but often uses this for. His 2020 book of 16 personal essays, OK, Let’s Do Your Stupid Idea, makes me think of Newkirk’s point, though this collection is nothing like Mukherjee’s book. Instead, it is just good to be aligned with Freyne’s sensibility for the duration of the essays. Yes, he can be very funny (a talent built on fine timing and self-deprecation), but his deeper purpose is the telling of stories, some of them his own. As Newkirk writes,

Narrative is the deep structure of all good sustained writing. All good writing.

This tenderness with the narratives of others’ lives can be seen in the outstanding piece right in the middle of the book, ‘Care’, in which he recounts his experiences in his 20s of working with intellectually disabled adults (‘I was a bit lost and in need of money’), stating that

It’s a beautiful thing when you realize it’s something you can do: physically care for a stranger.

Unlike the patients, he was able to move on, of course, to his current profession, admitting that ‘in journalism, when you care, you care from a distance’.

The previous piece, ‘Brain Fever’, is ‘a catalogue of mental-health difficulties’: two pages on Depression express the condition brilliantly for those of us who have not experienced it.

Another favourite piece for me was ‘Talking to Strangers’, on approaching strangers in public as a journalist and ‘strip-mining’ them. Famous people too, though they tend to be less interesting:

Sometimes when talking to a stranger, it’s hard not to find yourself being deeply moved. I have sat and listened to the saddest stories told to me by people who didn’t deserve to have sad things happen to them.

In his own story of not becoming a father, ‘Something Else’, Freyne writes eloquently through and then past the sadness:

I’ve thought in the past that it was a sort of grief that I’d been recovering from. But as I feel more optimistic about things, I’d amend that. It’s a type of love, a type of love I now hope to put to use elsewhere.

Much of that feeling is in this collection, which is full of the way Freyne notices, contemplates and values. Accompanying him is most enjoyable.