Deborah Levy's Living Autobiography

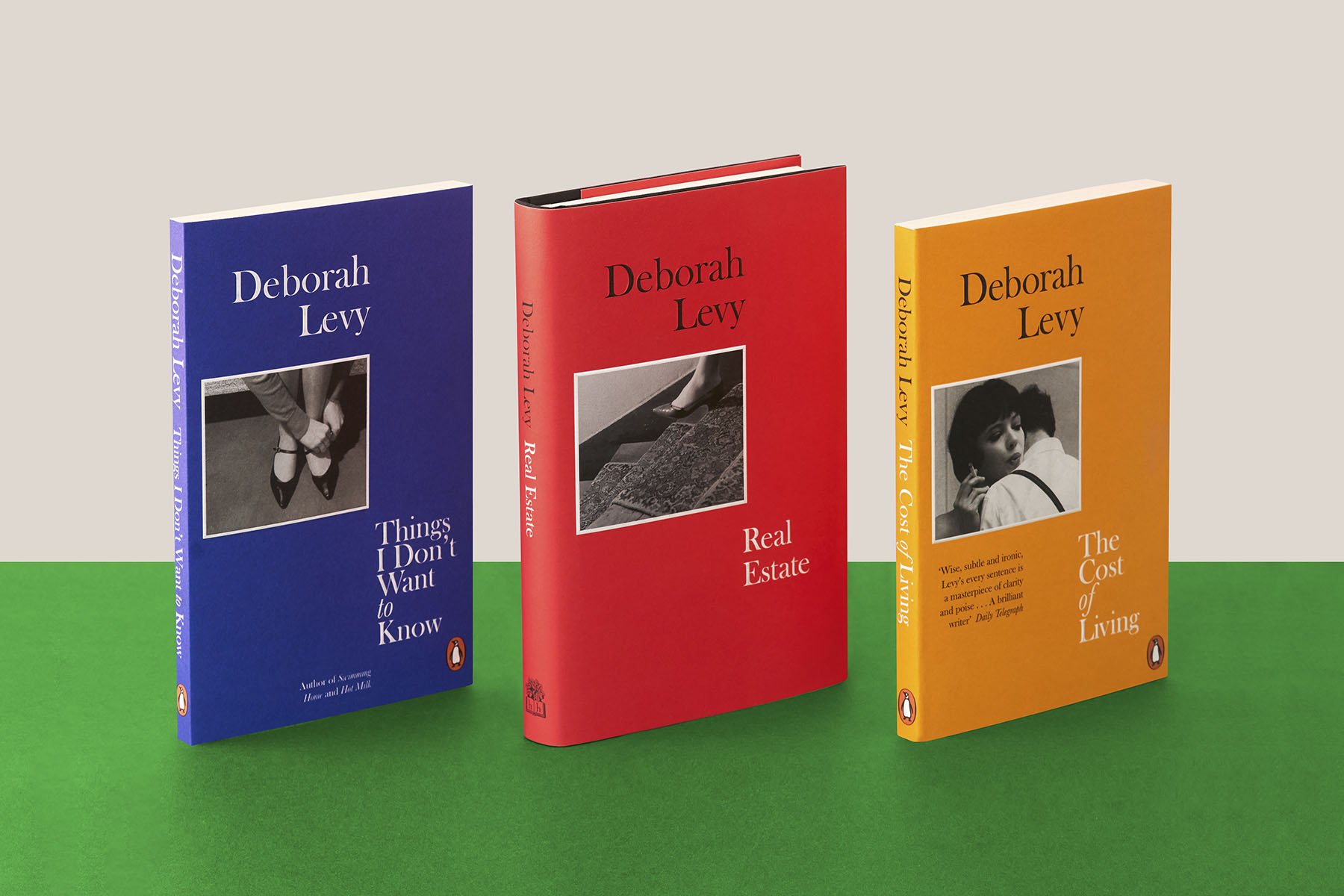

Over the last eight years Deborah Levy has written three volumes of what she calls her 'living autobiography'. The first, Things I Don't Want to Know, came out in 2013 as a response to George Orwell's essay Why I Write, in four sections.

It's short, sharp, and memorable. Best of all is the longest section, 'Historical Impulse', a vivid account of Levy's childhood in South Africa, which starts: It's snowing in apartheid South Africa. It's snowing on a zebra and it's snowing on a snake. The third section, 'Sheer Egoism' sees the family in England in 1974, having emigrated (Levy's father, an anti-apartheid activist, had been imprisoned in South Africa, and the family moved after his release).

These two pieces are sandwiched by descriptions of Levy in a chilly Majorca having in turn left London (first sentence in the book: That spring when life was very hard and I was at war with my lot and simply couldn't see where there was to get to, I seemed to cry most on escalators at train stations.)

The second volume (2018) has the perfect title which could stand for the whole trilogy: there is always, inevitably, a cost in living, and we have to pay it, and accept that fact. In this book Levy really finds her stride with a fluid reflection on the past and the present, particularly as a woman, and mother, whose life has become faster, unstable and unpredictable as her marriage breaks up, followed by a move to a new home (the central preoccupation of the final volume, Real Estate).

Throughout, there are brilliant moments, like the account of her visits to a newsagent run by three Turkish brothers to buy a particular flavour of ice lolly for her mother as she dies in hospital. It perfectly captures the temporary derangement that grief can cause.

The most expansive volume is the final one, Real Estate (297 pages, compared to 187 for The Cost of Living and 163 for Things). As she nears the age of 60, there is a stock-taking as she seeks a home to call her own, finally, and to put more shape on a life she had not expected to be still uncertain and even melancholy:

I was also searching for a house in which I could live and work and make a world at my own pace, but even in my imagination this home was blurred, undefined, not real, or not realistic, or lacked realism … the wish for this home was intense.

Like the previous two volumes, Real Estate is a freewheeling commentary on things, on places (Mumbai, New York, a new apartment for her while working in Paris, Berlin, Hydra as well as London) and brilliantly-sketched friends (mostly women, including Celia Hewitt, widow of the poet Adrian Mitchell, one of the few women I knew who was very like herself, but also ‘my best male friend’). A particularly enjoyable episode sees her buying special things for a special birthday of a friend who lives in Berlin. She sources a vintage fountain pen, an expensive bottle of Carob of Cyprus ink, the best marron glacés, and a soap in the shape of a cicada, spends a long time making a thoughtfully-personalised card, and wraps everything up in orange tissue paper, tied with flamboyant orange ribbons before heading to the airport for the celebratory weekend. You’ll need to read Chapter 10 to find out what happens next, which is funny and touching.

Finally she is in Greece, writing in her rented house, and comes to a realisation about what is her true foundation, her ‘real’ estate:

I wrote every day in its long, timbered attic and finally acknowledged I did not have a tranquil relationship with language because I am in love with it. I asked myself, what sort of love? Language is a building site. It is always in the process of being constructed and repaired. It can fall apart and be made again.

Across these three terrific books, Deborah Levy opens up to us the mind of a writer with honesty, sharp humour and enormous skill.