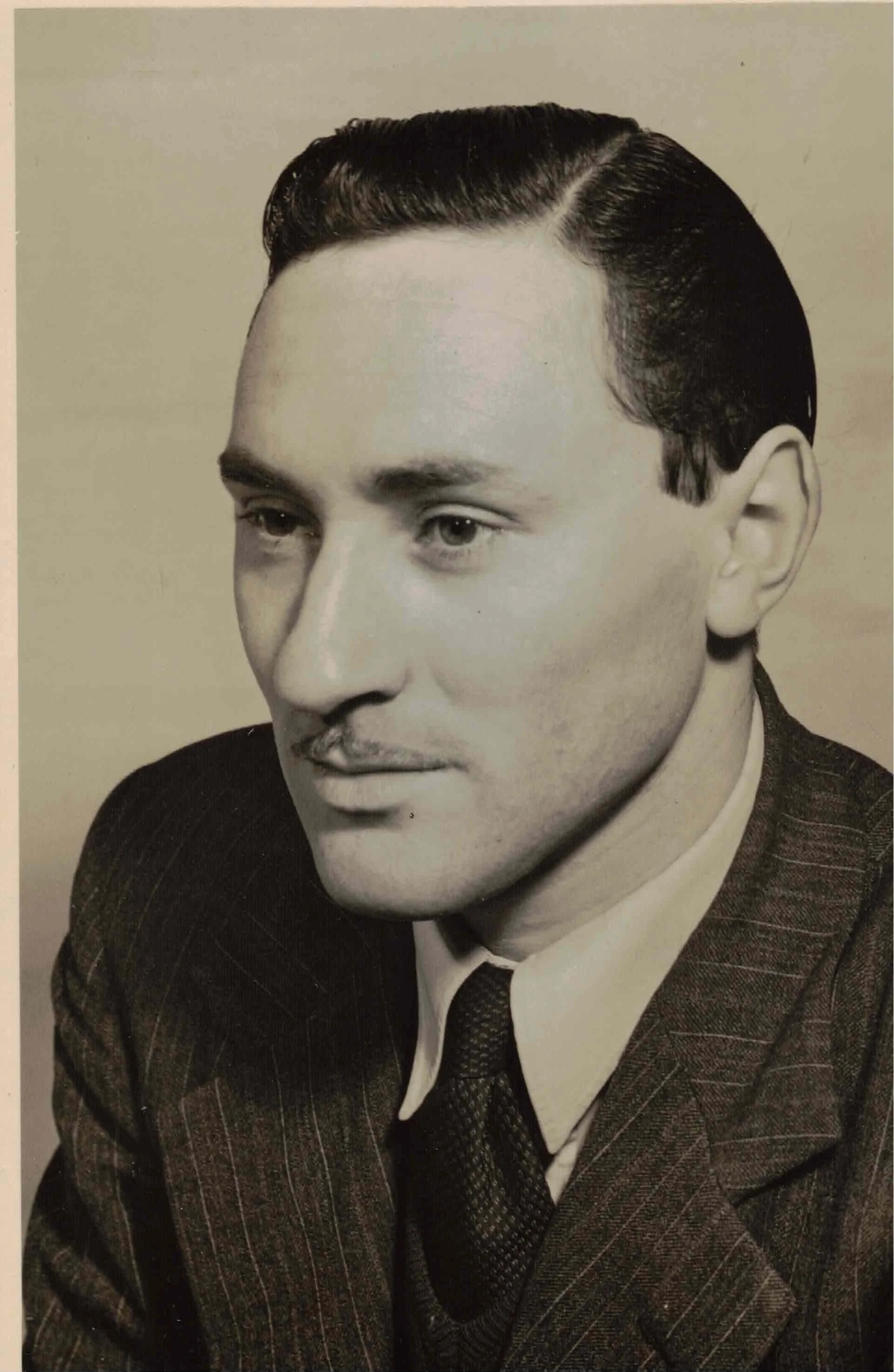

David Marcus: Editing Ireland

I took the bus into town. I was 18, and a few days earlier I had received in the post a neatly-written letter, asking me to come to the Irish Press offices in the centre of the city, beside the River Liffey on Burgh Quay, to talk to the Editor of New Irish Writing, David Marcus.

Like so many writers in David Marcus: Writing Ireland, a volume edited by Paul Delaney and Deirdre Madden for The Stinging Fly, and published 100 years after its subject’s birth, I made my way from the reception desk up the stairs to that small office, and like so many others I was greeted and treated with such courtly kindness and serious attentiveness by the great man, and with not the slightest sniff of condescension. I was 18! I had been reading the page for a couple of years, and noticed particularly an occasional Junior section, thinking maybe I could get something in there. So I sent some poems along, definitely not expecting any interest, let alone quick acceptance and publication on the full adult page.

As Michael Harding writes, getting such a letter from Burgh Quay was like reading something from Moses. Harding was even younger than me.

So on June 9th 1979 my poems ‘Maskings’ (a sequence of three sonnets), ‘Act of Nakedness’ and ‘Nightmare’ were published, taking up the whole right-hand strip of the page alongside a story by Brian Power. They were overly influenced by the two writers who meant most to me at the time, Heaney and Hopkins, but somehow David Marcus saw some promise in these juvenile works. He went on to publish more - two more poems in October 1979 (beside Sebastian Barry’s story ‘Lamb’) and on February 9th 1980 (‘His first poems to be published were in this page last year’ - and across the page from John Montague!).

And in April 1980 this most acute judge of short stories published ‘Tangents’, followed by another. Somehow he never turned down anything I sent in.

New Irish Writing departed the Irish Press in 1988 (the newspaper itself closed in 1995) and moved to the Sunday Tribune under Ciaran Carty, where space was found for more of my stories. These included ‘The Guest’, which won one of the three Irish Hennessy Literary Awards in 1989 (pictured below, my trophy), the overall winner being Joseph O’Connor, after judging by Piers Paul Read and Brendan Kennelly. New Irish Writing found further life over the years in the Irish Times and the Irish Independent, and its extraordinary and continued resilience says good things about our literary life, but also of course about the man who founded and nursed the concept for so many years.

This is a generous volume, full of generous commentary about a generous man. The editors call him, in the first sentence,

The most influential literary editor in Ireland in the twentieth century.

That is incontestable. No-one else comes close, and in the succeeding pages it is proven: Marcus had a huge influence on the careers of so many writers in our now-flourishing literary eco-system, and many of them here write tributes. Over and again writers refer to the qualities that as a callow young man I witnessed in Burgh Quay: his self-effacing modesty, and his extraordinary attentiveness to the way writing works, or does not.

Dermot Bolger’s lovely piece at the start, ‘David Marcus: a life’, is a perfect tribute in just 12 pages. He traces Marcus’s career from the start in Cork’s Jewish community through the founding of Irish Writing to the ‘New’ version that became legendary, and then to his declining years, which David’s own family - his wife Ita Daly and his daughter Sarah - describe so movingly at the end of the book.

Somehow the DNA of what David founded in his professional life was so resilient that it survived a series of homes in national newspapers, and is still with us in the Irish Independent. That foundation was based on what the editors rightly call his ‘exceptional judgment and instinct’. Tim Pat Coogan later refers to him as ‘a great encourager’ and ‘an enabling man’. He says simply

People liked him and he was very human.

That should do as an epitaph for any of us.

In our current coarse world (how coarse it feels right now), it is so cheering to read of someone who was so completely decent, in Mary Morrissey’s words ‘fastidiously courteous’. He seems never to have made any enemies in a notoriously bitchy environment. One reason, I guess, was his absolute honesty in assessing the quality of writing, and the unimpeachable - fastidious - fairness he exercised in his judgments.

There are many marvellous pieces in this generous volume, including the funny piece by Marcus himself recollecting his journey to visit Edith Somerville in West Cork, where he was greeted by her nephew, the Chaucer scholar Neville Coghill, whose translation of The Canterbury Tales I still use in class. There are quite rightly stories, too, by the likes of Desmond Hogan, Sebastian Barry, Mary Dorcey, Claire Keegan and Kevin Barry, the latter two being writers he was among the first to recognise. Many writers refer to the importance of his Jewishness, and how much of a ‘hyphenated’ person he was. He was of course an Irishman of a certain time, but you have to think that the other side of the hyphen, his belonging to the tiny community of Jews here, and the consequent way he came at his Irishness a little obliquely, must have been something to do with his encouraging of writing by women, and indeed in one collection, Alternative Loves (1994), by gay and lesbian writers.

The current blossoming of Irish writing is due in no small way to the seeds David Marcus sowed. He lives on in what Angus Cargill of Faber calls the explosion in Irish fiction writing. He lives on too, very fondly, in the memories of those whose lives he touched, however briefly, and of course in the hearts of his wife Ita Daly and his daughter Sarah Marcus (whose piece near the end touched me so much).

In an anecdote in that early piece, Dermot Bolger tells of the latter years, when David Marcus’s mind was failing, and how he had one last discovery to make:

It was sad but in another sense joyful and fitting that his last literary discovery, made in the closing years of his life, were the poems of a poet who spoke directly to him: a young Jewish poet growing up in Cork during the war. While sorting through his study, Marcus found an envelope untouched for years that contained a hundred typewritten poems.

They moved him deeply. Right at the end he discovered the name of the author which was, of course, David Marcus. As Dermot Bolger writes, that was indeed joyful: the young man had come back to life from across the decades. And now, 100 years after his birth, he comes back to life in this very fine volume.