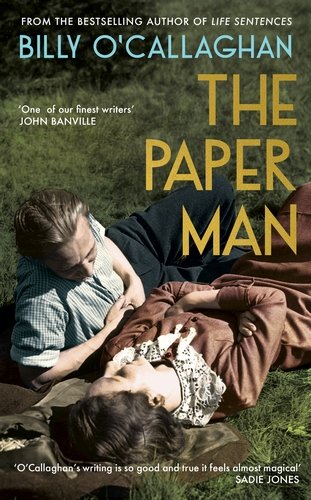

Billy O'Callaghan's 'The Paper Man'

Three people in particular are brought to life in Billy O’Callaghan’s new novel The Paper Man. One is brought back to life: Matthias Sindelar died in contested circumstances in Vienna in 1939, at the age of just 35 after a career which came very close to winning Austria the World Cup in 1934. By the time the 1938 competition took place in his country had ceased to exist, being subsumed by Germany in the Anschluss.

The other two are fictional: Rebekah was his young Jewish lover who he sent out of the country for her safety, arriving in ‘Jewtown’ in Cork City to be taken in by relatives she had never met. She did not know then that she was carrying the third person, their son Jack, who bridges the two in this story, still riven by loss by the early death of his mother and now (in adulthood, a docker) searching for the truth about his past.

The Jewish world of Vienna pre-war and the subsequent catastrophe that fell on it are familiar in literature (for a fascinating history of the same milieu in an Austrian city I know better, Innsbruck, see Meriel Schindler’s The Lost Café Schindler). However, Billy O’Callaghan presents the city with a fresh eye through the story of Sindelar, a brilliant but largely forgotten footballer; though he moved in Jewish circles, he was in fact Roman Catholic. In the so-called Anschluss match in April 1938 against Germany, an account of which opens this book, he refused to play along with the official narrative. A famous womaniser, in O’Callaghan’s story he falls deeply for Rebekah when he visits the tavern in which she works. The novel see-saws between Vienna and Cork, a poor and unpromising place as Rebekah arrives in the late 30s: but she finds great kindness and love in her relatives in Jewtown (the title of Simon Lewis’s first collection of poems, which evokes the now-vanished community).

O’Callaghan draws together the two sides of the story beautifully. His prose is poised, tender, sympathetic; it has a touch of William Trevor. Other characters are memorable too: Sindelar’s still-living friend Gustav Hartmann, Rebekah’s Cork relatives and Jack’s father-in-law Samuel, who accompanies him on the 1980 fact-finding trip to Vienna which concludes the novel. The author’s care with his characters can see in the moving attention he pays to a peripheral figure, the recent girlfriend found in Sindelar’s bed when he died, who herself died a few hours later:

Camilla Castagnola - an Italian prostitute, so the papers claimed, as though, even if true that defined the entirely of who she was. Not a heart that had chased to its own beating and felt happiness, fear and hurt the same way all hearts did but fodder for a story, and worthless beyond her sensationalised part in a sordid five-minute scandal. Thinking of this brings Jack a rush of sadness that on one level strikes as wildly overblown but on another, deeper level as thoroughly honest. Because what was her story, and what had life and the world been like for her?

The Paper Man is suffused with that kind of empathy. Sindelar got his moniker from his supposed physical frailty on the pitch, an idea he disproved over and again in his career. The other paper characters here also have at their core the strength of realised human beings, the entirety of what they are.