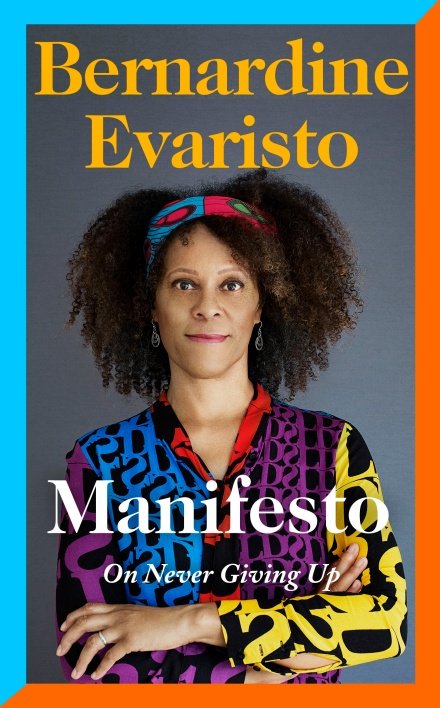

Bernardine Evaristo's 'Manifesto'

April/May 2020 was a strange and disconcerting time. With no idea of what was to come, we were experiencing our first-ever ‘lockdown’. This came at the same time as a stretch of truly stunning weather. Day after day there were blue skies and sunshine highlighting the lushness of the Irish countryside. Belatedly, I came to the writing of Bernardine Evaristo in the form of her Booker Prize-winning Girl, Woman, Other, reading most of it outside in the garden while basking in the warmth. Here was art as consolation, exhilaration in writing. It felt as if the book was made for that particular moment in its freewheeling generosity, its openness to human experience and its portrayal of the busy complexity of urban life. That was just what we wanted: it was a reminder of what we were missing, at a time when you could drive to the supermarket and pass just three cars on the way. Some day , we hoped, we would return to that plenitude.

It ends:

this is about being

together.

No better way to finish a novel which, as so many of us are apart, lifts the spirit.

GWO led me on to Mr Loverman, more conventional in form than the fusion fiction of the award-winner, but again hugely enjoyable:

in the last words of the book Barry (literally on a journey at the time) is advised to ‘sit back comfy and easy and listen to the one and only Miss Shirley Bassey and let we just enjoy the vibes, man, enjoy the vibes.’

This was followed by The Emperor’s Babe (so different once again - Roman London coming alive again in fizzy blank verse) and Blonde Roots (imagining the white slave woman of Chief Kaga Konata Katamba I).

That whistlestop tour of four books is to give the context behind Evaristo’s autobiographical Manifesto: On Never Giving Up. The Booker Prize did what it should, and opened up Evaristo’s writing to the general public in a spectacular way. Manifesto explains what led up to that ‘overnight success’, not just one but a series of intertwining journeys through creativity, sexuality and race. A particularly moving strain is on her father, tenderly described as the best father that he could be, despite his faults. She writes on all this with absolute honesty, and with the cheering confidence of someone who knows who she truly is, and who knows that her character is established and unswayable. In 190 pages she traces where her self-protective force field came from, and how eventually she arrived at GWO:

I could not have written this novel when I was a young woman because I was only interested in creating young characters. I’m always amused when my young students create frail, old characters hunched over walking sticks, only for them to tell me that they;’re in their forties. I would have been the same. It’s only now that I’ve lived a lot, listened a lot, experienced a lot and witnessed a lot - especially in my relationships and interactions with black women - that this book became achievable. I completed it when I was sixty years of age - with a substantial past behind me and facing a future of fewer years than I’ve already lived.

Start with the novels, and then you’ll find this personal account all the more enjoyable.