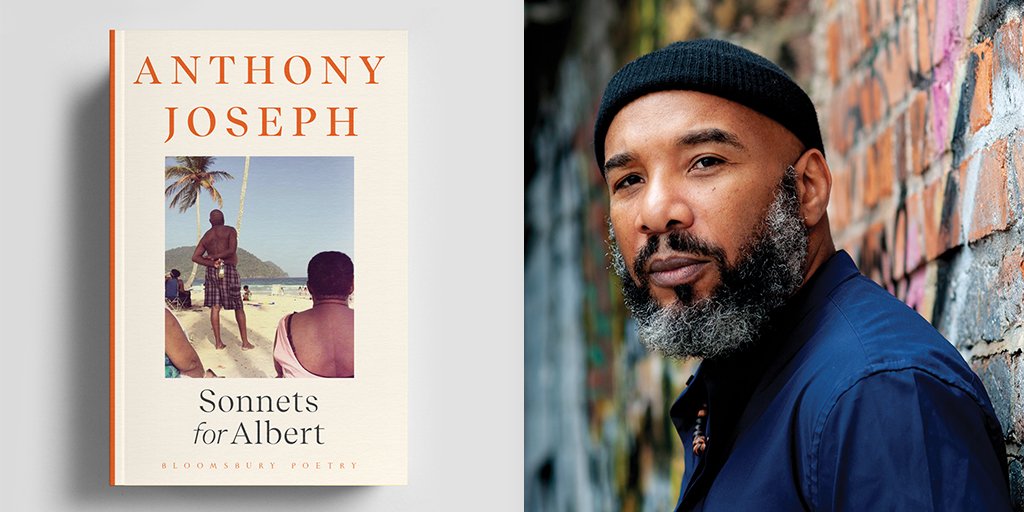

Anthony Joseph's 'Sonnets for Albert'

When I hear my father dead,

I flew ten hours into the sun.

The first two lines of the first poem in Anthony Joseph’s collection Sonnets for Albert (which won the 2022 T.S.Eliot Prize for poetry) tell us the direction this book will be heading: straight into the heat of emotion, straight into what being a ‘son’ means. Like Hamlet, who is ‘too much ‘i th’ sun’, the poet tries to make sense of a troubled paternal heritage. His late father was to a great extent a mystery, a man who abandoned children (he left Trinidad at one point for another family in Tobago), and these poems are attempts to (re)create him, to make sense of what his son now feels about him.

Late in the collection in ‘Memory Ghost I’ Anthony Joseph thinks of his own daughters, and hopes that

there is time still

to shape the ghost

that must enter their memory.

when he dies, his book an attempt to form an understandable shape out of the ghost in his own memory.

He opens with Albert’s death, but then weaves in and out of images from his past, the flexible sonnet form moving fluidly from standard English to Caribbean argot, interwoven with evocative black and white intimate family photographs of the father. Albert stands, now big-bellied, stirring a pot in a small kitchen in Santa Cruz in later life in 2014; overleaf as a young slim man he stands beside his new (and heavily pregnant) bride in their wedding finery in 1966, nervous and bright-eyed facing into a future which will disappoint. In ‘Broadway’ his son asks

You don’t have no shame fathering all these children?

And now that his father’s ‘life force’ has left, Anthony asks:

But is a long time now we forgive you, Albert.

Not for what you was not, but for who you promise

to be and unfulfil.

That promise went all awry. In ‘Tobago Family’ he hears of a third brother on that island:

Like our father,

the grist and very mystery of blood.

All the many versions of that mystery of a life are here: the young ‘player’ of women, the preacher in New York City, the reduced self in his seventh decade. The fragments of memory slowly build up like shards re-forming a broken portrait, facing a confusion rooted in a now unalterable childhood:

And I never called him ‘Dad’ or ‘Pops’ or ‘Father’.

False formally as ‘Mr Joseph’, more often, but mostly

I avoided calling him anything at all. (‘Stones’).

Now the ‘calling’ is different: in hospital late on (‘P.O.S.C.H. II’) his son thinks of how his father’s absence in Tobago for so long ‘eat up all the joy’, but it is the older man who anxiously wants the attention of the son he neglected so badly in childhood:

When I tell him I will call him tomorrow,

he makes me promise that I will. He says,

‘Sometimes you say you will call

and you don’t.’

All parents are to some extent mysteries to their children; there were all those years when we were too young, too self-absorbed, too innocent to see more, perhaps understanding them more as adults only when we ourselves are no longer children. In this collection ranging from when the poet was a gap in language in that wedding photograph to the moment that first dirt dash the casket lid, this son shapes his memory ghost with honesty, control and grace.